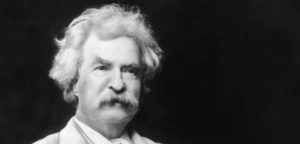

Mark Twain said that comedy is “tragedy plus time,” but where’s the comedy in the middle of the tragedy? And we’re all familiar with the concept of whistling past the graveyard. But how can you create comedy when you’re stuck in the middle of the graveyard, and there doesn’t seem to be a way out?

We’re all feeling the stress. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, more than a third of American adults reported symptoms of an anxiety disorder; last year it was less than one in twelve. Recently, the Kaiser Family Foundation released a tracking poll showing that for the first time, a majority of American adults — 53 percent — believes that the pandemic is taking a toll on their mental health. There’s been a 20 percent rise in domestic violence incidents. 36 percent of Americans report that coronavirus-related worry is interfering with their sleep, 18 percent say they’re more easily losing their tempers, and 32 percent say it has made them overeat or under-eat. I don’t have the statistics, but I’d bet that alcohol (and other substances) consumption is up, as well as incidents of domestic violence.

These are the hardest times to do comedy, but

they’re also the times when we need it the most.

Maybe that’s why comedy was invented.

– Jimmy Fallon

By now, we’re all familiar with Norman Cousins and the therapeutic effects of laughter. And it’s not just anecdotal evidence: According to the Mayo Clinic, laughter “enhances your intake of oxygen-rich air, stimulates your heart, lungs and muscles, and increases the endorphins that are released by your brain.” Moreover, laughter can release neuropeptides help fight stress and reduce anxiety and help the body generate its own natural painkillers. Scott Weems, a cognitive neuroscientist and the author of “Ha! The Science of When We Laugh and Why” writes that laughter “releases bursts of dopamine, a hormone and neurotransmitter that signals pleasure and reward, and studies have indicated that it also can improve blood flow, immune response, pain tolerance and might even shorten hospital stays.”

In these stressful times, humor can relieve stress, and divert us during hard times. But can comedy do more than just distract us while we’re quarantined?

Whoever has cried enough, laughs.

– Heinrich Mann

Comedic arts can do more than simply deflect, turning trauma into punch lines; comedy gives us the tools and the means to, as Freud put it, “express the otherwise inexpressible.” Comedy can help us process tragedy, by bringing us a broader view and alternative perspectives.

But aren’t there some things, some events, that are too horrible, too tragic, for comedy? Where comedy is gratuitous, in bad taste? Like a pandemic, or 9/11 or the Holocaust.

There’s actually a great documentary on comedy and the Holocaust, called The Last Laugh. And in The Last Laugh, comics like Mel Brooks, Sarah Silverman, and Larry Charles, as well as survivors of the Shoa, ponder the age-old questions of comedy and tragedy. According to one survivor, “Without humor, we wouldn’t have survived.” Humor played a large role in mental survival and stability. It counteracted the deception and lies, because it was real.” Humor, and the laughter it provoked, provided an alternative way of internalizing abnormality, a defense. As Jerome Zolten writes in “Joking in the Face of Tragedy, “In the face of tragedy, comedy creates community, connecting people dealing with disaster.” Or as Mel brooks put it, “humor is just another defense against the universe.”

There’s actually a great documentary on comedy and the Holocaust, called The Last Laugh. And in The Last Laugh, comics like Mel Brooks, Sarah Silverman, and Larry Charles, as well as survivors of the Shoa, ponder the age-old questions of comedy and tragedy. According to one survivor, “Without humor, we wouldn’t have survived.” Humor played a large role in mental survival and stability. It counteracted the deception and lies, because it was real.” Humor, and the laughter it provoked, provided an alternative way of internalizing abnormality, a defense. As Jerome Zolten writes in “Joking in the Face of Tragedy, “In the face of tragedy, comedy creates community, connecting people dealing with disaster.” Or as Mel brooks put it, “humor is just another defense against the universe.”

Comedy isn’t about making fun of tragedy. It’s about talking about how humans behave, even in the face of tragedy.

In The Last Laugh, Sarah Silverman says that “Comedy puts light onto darkness and darkness can’t live where’s there’s light. That’s why it’s important to talk about things that are taboo, because otherwise, they just stay in this dark space and they become dangerous” A little later in the film, Larry Charles, one of the writers of Seinfeld and the director of Borat says that comedy in situations like that “touches the dark part inside, —the taboo joke allows you to purge and have a catharsis. People subconsciously need to tap that dark part, that id-like part of their psyches.”

When asked about humor and the Holocaust, Elie Wiesel said that “There was nothing categorically funny about their situation, but in order to survive, they had to look at their circumstances through a different lens.” And as one of the other survivors later in the film put it: “It would be a horrible life for me for 70 years to just cry.”

Mel Brooks summed it up best:

“Tragedy is when I cut my finger.

Comedy is when you fall into an open sewer and die.”

In March of this year, Alain de Botton, a British philosopher, wrote an extraordinary Op-Ed in The New York Times entitled Camus and the Coronavrus. You might remember that Camus famously wrote about an infectious disease that passed from animals to humans that devastated a small city in French Algeria, The Plague. Botton writes that Camus, to prepare himself to write the book, “immersed himself in the history of plagues. He read about the Black Death that killed an estimated 50 million people in Europe in the 14th century, the Italian plague of 1630 that killed 280,000 across Lombardy and Veneto, the great plague of London of 1665 as well as plagues that ravaged cities on China’s eastern seaboard during the 18th and 19th centuries.

“Camus was not writing about one plague in particular, nor was this narrowly, as has sometimes been suggested, a metaphoric tale about the Nazi occupation of France. He was drawn to his theme because he believed that the actual historical incidents we call plagues are merely concentrations of a universal precondition, dramatic instances of a perpetual rule: that all human beings are vulnerable to being randomly exterminated at any time, by a virus, an accident or the actions of our fellow man.

“Camus was not writing about one plague in particular, nor was this narrowly, as has sometimes been suggested, a metaphoric tale about the Nazi occupation of France. He was drawn to his theme because he believed that the actual historical incidents we call plagues are merely concentrations of a universal precondition, dramatic instances of a perpetual rule: that all human beings are vulnerable to being randomly exterminated at any time, by a virus, an accident or the actions of our fellow man.

“For Camus, when it comes to dying, there is no progress in history, there is no escape from our frailty. Being alive always was and will always remain an emergency; it is truly an inescapable “underlying condition.” Plague or no plague, there is always, as it were, the plague, if what we mean by that is a susceptibility to sudden death, an event that can render our lives instantaneously meaningless.

“This is what Camus meant when he talked about the “absurdity” of life. Recognizing this absurdity should lead us not to despair but to a tragicomic redemption, a softening of the heart, a turning away from judgment and moralizing to joy and gratitude.”

“A year from now, you’ll all be laughing about this virus,” reads one recent meme.

“Not all of you, obviously.”

In films such as Jo Jo Rabbit, Three Billboards . . . , Silver Linings Playbook, and Life is Beautiful, there’s no subject that can’t be approached in a comic vein. The often difficult part is finding the right purchase, the right angle of attack. You can’t make fun of tragedy; but you can find comedy, and our flawed humanity, in our myriad, sometimes crazy, sometimes ludicrous reactions to that tragedy. Jo Jo Rabbit is about Hitler and Nazis; Silver Linings Playbook is about mental illness, adultery, failure . . . and it is a wonderfully funny romantic comedy. Modern and post-modern comedy is often a precarious balancing act between tragedy and absurdity. But it’s part of our obligation as artists, as comic artists, to find that balance, and share it with our community. In his book “Following the Equator,” Mark Twain wrote, “the secret source of humor itself is not joy, but sorrow. There is no humor in heaven.” Comedy may come from sorrow, but it can also help and heal us. As one comic said, “There are tragedies that we can never laugh at, but we must laugh our way through them.

I’m reminded of a tale in the Talmud where the Prophet Elijah said that there will be reward in the next world for those who bring laughter to others in this one. Who are we to ignore a Prophet?

I’m reminded of a tale in the Talmud where the Prophet Elijah said that there will be reward in the next world for those who bring laughter to others in this one. Who are we to ignore a Prophet?

One of my favorite writers is Sholem Aleichem, a great Yiddish humorist of the 19th century, who once wrote that “Life is s blister on top of a pimple . . . and a boil on top of that. The world is full of miserable people creatures who do miserable things. So just for spite, I’m not going to cry. Just on spite, there’s going to be laughter.

Stay safe. Be well and be good. And create comedy.